#BlackLivesMatter: “Let Us March On…”

Photo by Kayla Cook

“Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on ‘til victory is won.”

-”Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” by The Johnson Brothers (James Weldon Johnson & John Rosamond Johnson)

INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 put a magnifying glass on several of America’s social issues this past year. One focus in particular was the continuous fight for racial justice for Black lives, prompted by high news coverage of stories of Black lives gone too soon such as the lives of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Prior to the pandemic, we were collectively focused on our daily schedules, overlooking bigger picture concerns. During the Summer of 2020, Americans understood we must be more active if we are going to enact real change in terms of racial justice. However, the surge of interest in the Black Lives Matter Movement, much like Americans’ reaction to the coronavirus pandemic, settled down once people decided they were “over it.” But neither issue is a trend. #BlackLivesMatter is not a trend. #BlackLivesMatter is a way of life.

Many Americans prefer to believe the American myth that any American can work their way up the social ladder with determination and hard work. But this view of hyper-patriotism is more performative than an accurate depiction of our country as a whole. Throughout history, and to this day, some white Americans victim blame, pointing fingers at Black people as the creators of the social issues which plight the Black community as if to say, “It must be their own fault they are stuck at the bottom.” But this system of beliefs blinds an entire population to the reality that systemic racism withholds Black people from equal rights and opportunities. Social structures against the Black community are strongly rooted in place, those roots centuries old. The social structures may have new disguises over the years, attempting to present simply as modern American necessities. During this time of pause, when COVID-19 is still such a threat to our country, American citizens are realizing a viewpoint of “I’m just not into politics” is an uninformed and uncaring viewpoint. It is time to reevaluate if particular institutions and organizations (prisons, law enforcement as we know it, etc.) are necessary, or necessary for white supremacists to utilize to continue to perpetuate a harmful hold on our country.

Living through this past summer as a Black American was so overwhelming. I initially started working on this blog post in June 2020. There are several reasons behind the prolonging of this post, but I am glad to finally publish it during Black History Month: a time to reflect, educate, and take a serious look at how we are shaping our nation with both action and inaction.

MY IDENTITY

Before we begin, the following is told through the lens of a Mixed Black 23-year-old American woman. Although visibly mixed-race, I primarily identify with my blackness, navigating the world as a Black woman, as I was raised by a single Black mother. I grew up in a small town in Kansas, where my family for some time were the only Black members of the community. I have never experienced the “white guilt” I hear some Mixed Black people talk about and “white-passing” never was and never will be a goal of mine. I not only embrace but lead with my blackness, the side of my heritage which raised me and offered a rich culture and empowering history.

Even so, please keep my identity in mind as a kind of “disclaimer” while reading. Although I have naturally experienced racism as a Mixed Black woman in America, I have not experienced racism in the same way or to the same degree as members of the Black community who may be a more hypervisable target for racism because their phenotype is more strongly associated with blackness.

Furthermore, I do not cover “everything” in terms of racism in this one blog post. How could I? However, I do cover the surge in #BlackLivesMatter related content on social media since Summer 2020, the importance of learning AND unlearning about racial justice matters, and the act of policing. I simply hope to remind people, especially young people, that you do not have to have all of the vocabulary or years of attending the polls to have a political opinion. For young people of color, we have experienced injustices due to problematic systems in our country that those who belittle our political opinions will never and could never understand. (But they can try.)

Enjoy. & Happy Black History Month.

-x, k.

Photos by Andrew Hughes

NOT A TREND

I love a good post of solidarity but when is it not solidarity but self-serving? And furthermore, silencing to the very community the post claims to advocate for?

On June 2, 2020, “Blackout Tuesday,” occurred on Instagram. Black screens overtook the photo-sharing app. The sea of black screens exposed selfies, extravagant food photos, staged travel pictures, and more for how these posts truly felt at the time: Empty. While intended as well-meaning posts of solidarity, the use of the Black Lives Matter hashtag (#BLM) on these several postings of black screens essentially erased the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, putting a slew of black squares in place of important updates and information for #BLM protestors. (Erased educational tools. Erased connections. Erased identities. In the middle of a pandemic when we need those things most.) Seemingly, a “Blackout Day” which was organized by Black women in the music industry was co-opted for the use of performance activism. While I felt physically sick watching the hashtag flooded with emptiness instead of resources, testimonials, art, and more, the trying day held an important reminder: Don’t stop questioning what is skillful propaganda and/or strategic social media planning. Don’t forget—Social media is a tool. Sharing misinformation or in this case, posting for the sake of posting prior to well-conducted thought, can actually hinder a movement. The use of social media in terms of education, awareness, and organizing activism can be helpful, the misuse, harmful. Let’s use it well.

Social media can be fun. Social media can be escapism. But in moments like we are currently in—this pandemic where we can pause and realize how we could actually dismantle systems of oppression—please, let’s not use “slactivism.” We’ve had the conversation about those in privilege refusing to acknowledge police brutality and racism, but have we had the conversation about those who will post followed by an archive or a delete later? Or only keep the post up to, “show they cared” to serve their own social media presence? I remember wondering how many users would delete or archive their posts once police brutality against Black bodies was no longer “trending,” a frustrating thought as I am Black even when #BLACKLIVESMATTER is not trending.

I have and will continue to “unfriend,” ”unfollow,” etc. people who have been on my socials for years, some for over a decade. I have to protect my own health. I encourage other social media users to do the same, putting their mental and emotional well-being first, even if that means being confronted by the person you remove from your socials later. A popular rebuttal to removing profiles which constantly post harmful misinformation or opposing viewpoints is, “But you of all people could help them understand!” As so many Black people have constantly told others (and remind ourselves)—It is not our job to educate non-Black people on the oppression of Black people. I remove users, unfazed, knowing time spent stewing over their posts or reading through the thread of comments could be spent on something more productive (like me finally finishing reading Angela Davis’ autobiography lol.)

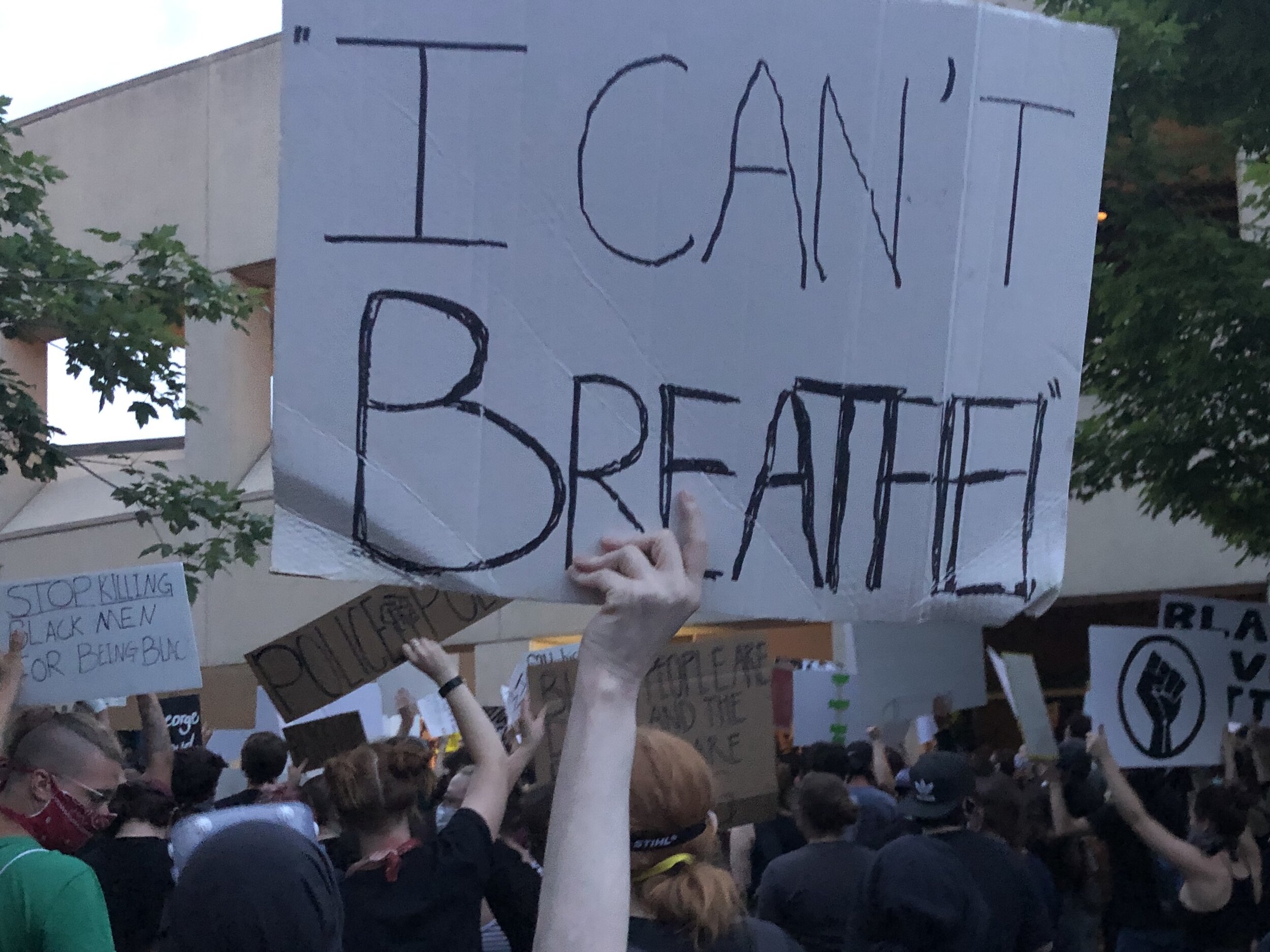

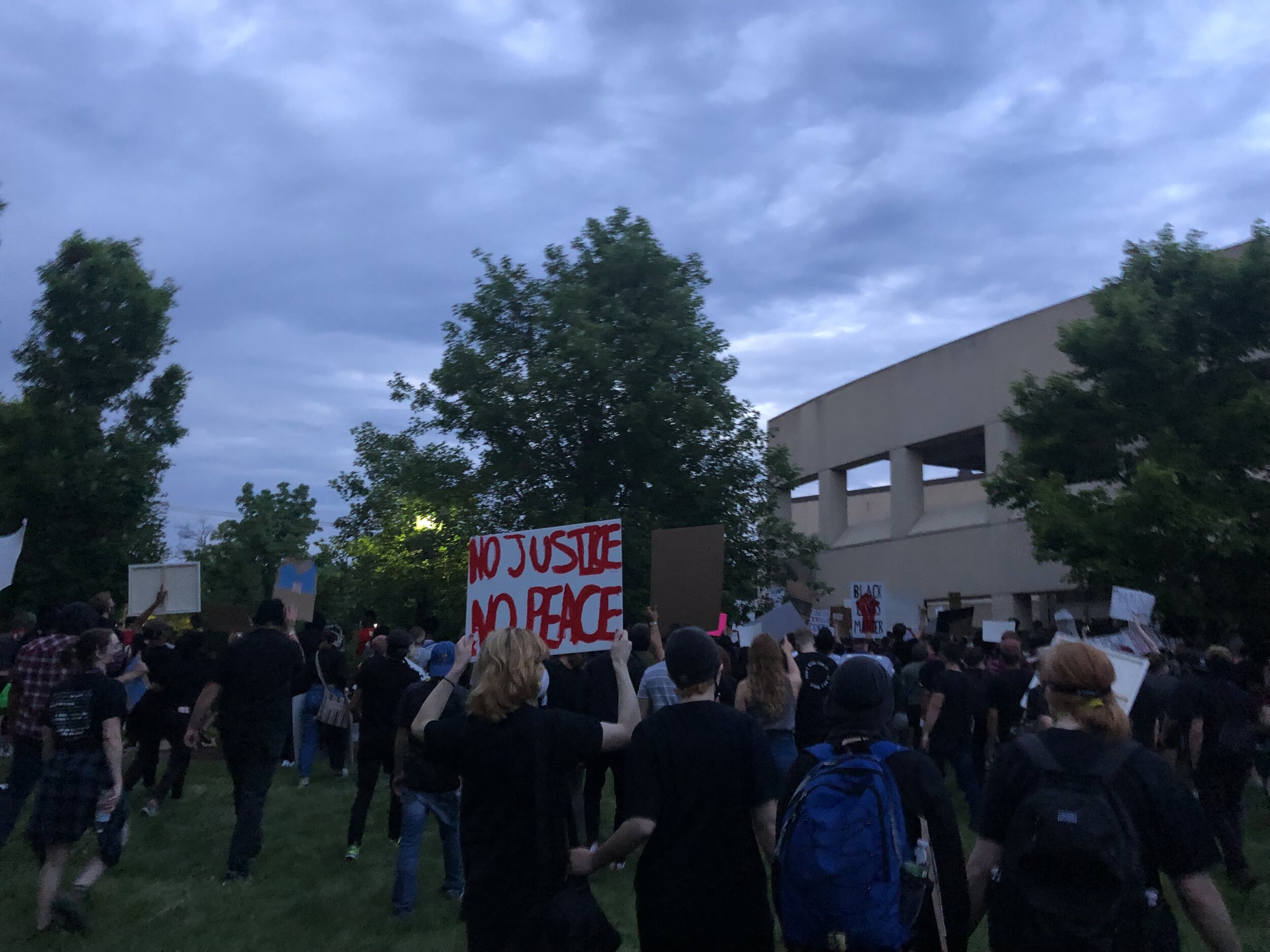

LFK Against Police Brutality March. Sunday, May 31, 2020. Lawrence, KS.

Photos by Kayla Cook (Shot on iPhone X)

EDUCATION

When attempting to individually ponder topics such as systemic racism and police brutality, it is easy to think, “Where to start?” Like most topics, research is a great starting point—especially when there is so much to not only learn but unlearn. This past summer, it was wonderful to witness the outpouring resources on understanding and advancing racial justice in America made easily accessible on various social media platforms. PDFs, YouTube videos, etc. at our fingertips. I hope we collectively revisit (or finally get around to) those bookmarked, pinned, or screenshotted posts this Black History Month. One of my favorite resources and a great place to start in terms of studying activism for Black lives is Assata, an autobiography by Assata Shakur. A large takeaway from this book for me was reevaluating the American history I was taught, which opened my eyes to how that education serves a nation with a thirst to uphold white supremacy.

Shakur, an influential Black female civil rights activist during the Black Liberation Movement, said,

“The schools we go to are reflections of the society that created them. Nobody is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them. Nobody is going to teach you your true history, teach you your true heroes, if they know that that knowledge will help set you free. Schools in amerika are interested in brainwashing people with amerikanism, giving them a little bit of education, and training them in skills needed to fill the positions the capitalist system requires. As long as we expect amerika's schools to educate us, we will remain ignorant.”

Personal Testimonies

I attended a high school where my history teacher told racist “jokes.” (Read that again. History teacher.) I attended a high school where I was called the n-word to my face for the first time. I attended a high school where a teacher minimized the Black community’s response to the racially motivated murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin because, “The shooter wasn’t white though.” I attended a high school where a white student actually asked, “What about us?” in a discussion concerning the Ferguson riots—an “All Lives Matter” rebuttal to a “Black Lives Matter” discussion.

I attended a community college where, in response to claims of racism, instead of accepting accountability for less than inclusive actions and promoting enacting change, the college’s statement labeled the claims as “bullying.” I attended a community college where the lives of young Black students are only valued if they are winning sports games but whose same lives are not valued once off the court or the field, displayed by how they are treated by law enforcement in the small rural town. I attended a community college where “those football boys” said in a derogatory tone is lingo for “Black male students” (or you could imagine the word some community members likely use behind closed doors.) I attended a community college where some community members chastise Black students for behaving in the same manner their white children do, in the manner young people do and have the right to live and learn and make mistakes and make memories.

I attended a university where I had my first Black instructor—during my senior year of college. I attended a university where learning about Black literature was a priority on the syllabus, not a neglected option (because Black literature is American literature.) I attended a university where I was allowed to take up space and provided with resources to step into my greatness. I attended a university where I am sure inclusion and diversity is still an issue in ways my particular experience did not bring to my attention. Although I was still often the only Black student in the classroom, I could be myself instead of hyperaware of being othered. Conversations on race did not end in me feeling gaslit and defeated but, instead, empowered and educated.

Educators must be willing to confront and fix their own prejudices and biases and, more importantly, schools must provide proper diversity and inclusion training. What does it say about the quality of a school’s education practices when American history is taught by a high school teacher known to make homophobic statements and racist “jokes”? What does it say when this person is shaping young students’ minds on how to view America’s past, present, and future? How to view others and themselves? Educators who do not do the work to overcome their internalized racism and prejudices, allowing their oppressive beliefs to manifest in the classroom, are a threat to proper education.

Education aids change. AmeriKKKa* doesn’t want to teach Black history—or any non-white history, LGBTQIA+ history, etc.—which we know make up the full American history. People who “got over” the “trend” of challenging the racial injustices in this country must make a decision: Broaden the scope of what you consider important issues. Then, take the time to research those issues in order to effectively discuss them with members of your communities. Leave behind the view of “not my problem.” Become a self-thinker. Crack open a book or watch a documentary—about an identity outside of your own. (Or continue to navigate our country from a surface level viewpoint.)

We talk about how having a past of racist comments/behavior does not make you a “bad person”—You were socialized that way and have since left those unfortunate misteachings behind. But, just a reminder, being vocal about social issues doesn’t give you a ribbon either. That is our job as Americans. We have these “great American ideals”—so let’s live up to them.

Education + Humanistic View + Personal Testimonies (publicly shared or privately shared) will help move us forward. This has to happen in tandem with signing petitions, texting and calling, VOTING, donating, confronting our racist friends and family members, and protesting (in whatever manner is fit for the particular situation—yes, including rioting.) What does Education + Humanistic View + Personal Testimonies equal? This equation equals healing from racial trauma and, for those who aren’t Black, confronting their own internalized (or not-so-much internalized) racism. Furthermore, this equation equals advancing our knowledge in order to more effectively fight against injustice.

*-a spelling used by Shakur for our nation to convey our country’s refusal to dissipate white privilege & white supremacy

Photos by Andrew Hughes

“STOP LOOTING OUR BLACK LIVES.”

This past summer, many Americans revealed that their obsession with wealth took precedence over racial justice by making the centerpiece of conversations on protests and riots “looting” instead of the fight for Black lives, Black rights, and Black dreams. Wealth inequality is only increasing, and many white people refuse to acknowledge their current and historical privilege. What are people really saying when they say, “I support this summer’s protests, but…”? They are saying: “I support the protests, but I expect Black people to still appeal to white people using respectability politics.”

In a college English course, a white student’s project was something along the lines of, “How Black civil rights activists of the 1960’s used language to appeal to white people in power.” Although well-meaning, I had to note that not all Black civil rights activists used respectability politics or wanted to “appeal” to white people in power. (Just the ones that are often favored in American classrooms.) And current activists should not be expected to “appeal” to white Americans either. This fight isn’t about white people and white comfortability. This fight is, again, for Black lives, Black rights, and Black dreams. And… How effective is “comfortability,” anyway? Neither approach is right or wrong, but our society acts as if one is (of course the favored approach is usually the one catering to white comfortability.) Historically, comfortability and change do not often go hand in hand. Confronting our country’s oppressive systems is not a comfortable act by any means. But in order to hold our country accountable to actually provide “Liberty and Justice for All”—value the lives, rights, and dreams of all—people are going to have to stomach feeling uncomfortable.

The phrases “Defund the police” and/or “Abolish the police” incite fear in many because law enforcement as we know it, prisons, etc. were framed as necessities. Along with reassessing how law enforcement currently functions and reassessing the amount of funds provided for law enforcement, we have to reassess how we were taught to police others. In Assata Shakur’s autobiography, she spoke of other Black women standing as guards at her cell, policing her, because they were promised a shortened sentence. Although also Black women, also imprisoned, they turned to policing another Black woman for the crumbs of returning to their previous way of life (in a still oppressive society) sooner. Reading this passage reminded me of learning about Black slave catchers who also appealed to white people in power for crumbs of rewards as well. Policing our own people, Black people within the Black community, happens, and we know it certainly does outside of the Black community. There are even Instagram accounts dedicated to collecting the slew of video clips and new reports of “Karens” and “Kevins” calling the police on innocent Black citizens to display the ridiculous nature of white privilege and racism. Policing with the ultimate goal of harm towards Black bodies and policing with the ultimate goal of self-advancement must come to an end. (Where is unbiased observation? De-escalating? Compassion?) The policing that American citizens have neglected most is the policing of our own minds.

Black people experience living “guilty until proven innocent” daily. To live “guilty until proven innocent” is to live under constant scrutiny under a racist eye. Dark skin, or other phenotype signifiers as “Black,” signify as “bad” in the eyes of racists until they “get to know you.” (That’s when you get the, “Oh, but you aren’t like them” behavior.) We all collectively must unlearn the intentional subtle (and not-so-subtle) teachings of signifying lighter skin as “good” and darker skin as “bad.” Even people of color, people within our own communities, perpetuate colorism. In American society, the media showcases white people as kind of “main characters” or “next-door neighbors” everyone should like, depend upon, and root for. White people are considered “default” and “like that person on TV who could be my friend.” The “Good Guys.” Whereas a false narrative carefully crafted Black people as the “Bad Guys.” Assumptions that Black people, as a race, are innately “bad” are due to a history of criminalization through racial propaganda and generations of word of mouth biases. We must collectively and actively work to dismantle this inaccurate narrative and the oppressive systems that uphold it. America has two options: to manifest the ideal of “The Land of the Free” offering the “American Dream,” or to continually lie about who we are as a country.

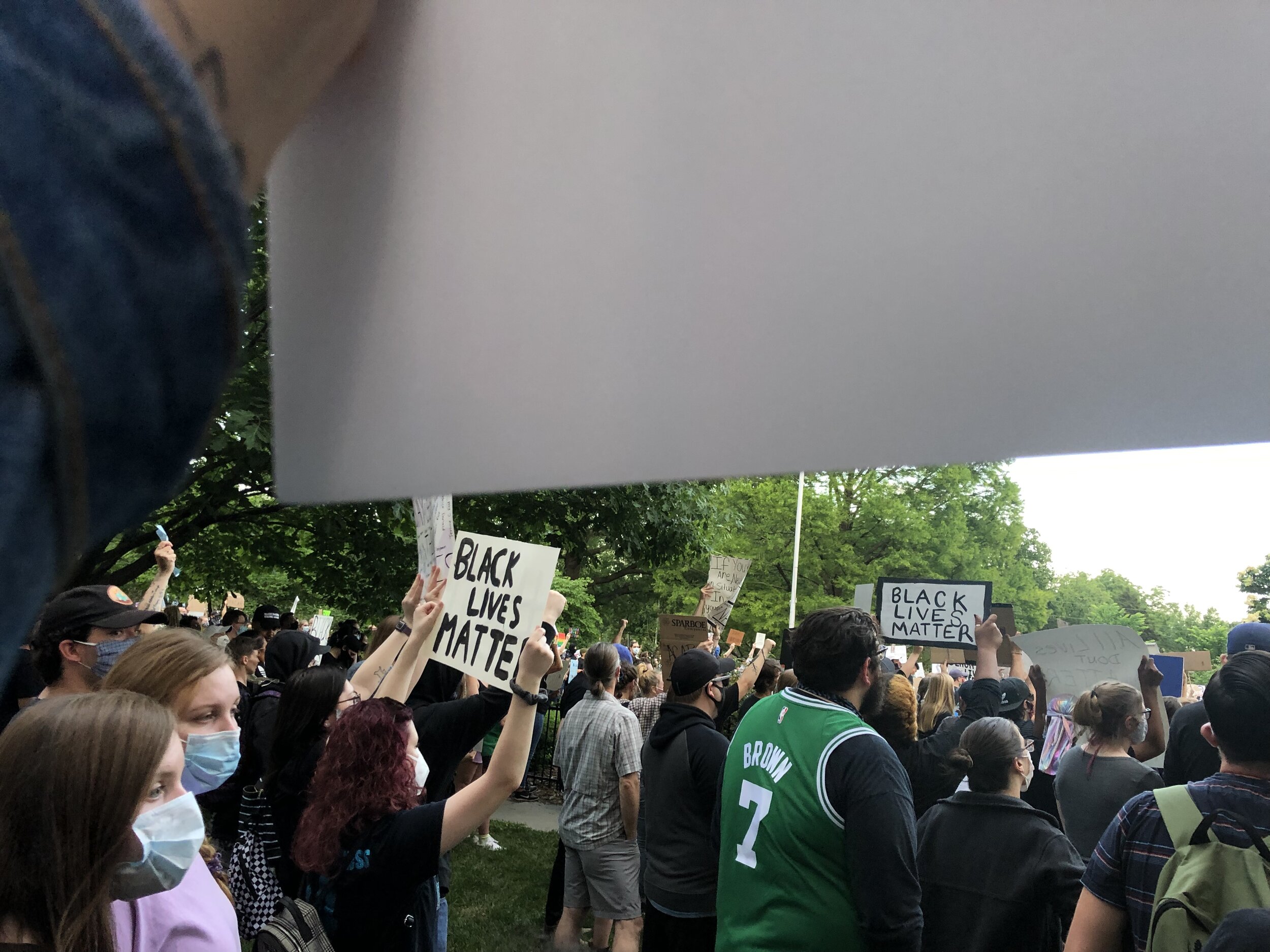

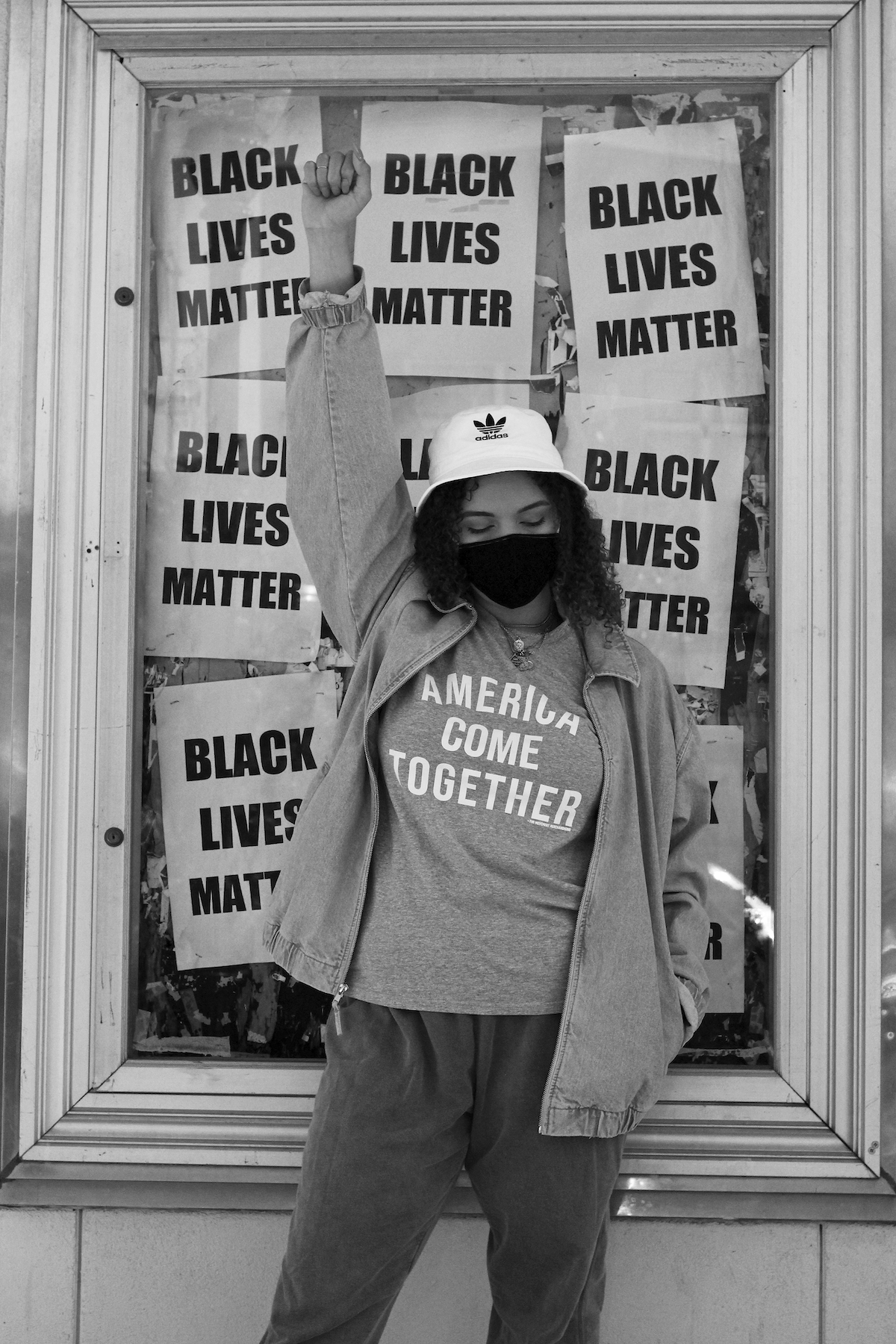

Black Lives Matter: Reallocate KCPD Funding Protest. Saturday, June 13, 2020. Kansas City, MO.

Photos by Kayla Cook (Shot on iPhone X)

“LET US MARCH ON…”

We have seen a lot. Let us add our contribution to the mural those who came before us started, hoping for an end result they never got to see. We may not see the finished painting either, but we can add our colors.

To save y’all $2,000: Here is a list of books I read in ENGL 340 (Literature about Black Freedom Struggles) and ENGL 598 (Reading Race in American Literature: Jim and Jane Crow—Then and Now), as well as a few “Common Books” from previous years used by my alma mater. (If reading feels heavy during this time of the pandemic, you can download several audiobook versions of the following through your public library using the Hoopla app.) Also, I listed a few of my favorite Black creatives I discovered over the years. (Some in classes, some not!) Feel free to add other Black Art in the comments!

Peace & Love,

-k.

BLACK ART

ART

Jean-Michel Basquiat

David Hammons

Glenn Ligon

Adrian Piper

Faith Ringgold

Kara Walker

Fred Wilson

AUTOBIOGRAPHIES

Maya Angelou, A Song Flung Up to Heaven

Assata Shakur, Assata

COMMON BOOKS

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me

Claudia Rankine, Citizen*

DOCUMENTARIES

American Denial: The Truth is Deeper than Black and White

I Am Not Your Negro

Mississippi: Is This America?

Two Societies

FILM

13th*

Just Mercy

Night Catches Us

When They See Us

NOVELS

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Charles Johnson, Dreamer

William Melvin Kelley, A Different Drummer

Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon

Denise Nicholas, Freshwater Road

Ann Petry, The Street

Angie Thomas, The Hate U Give

Alice Walker, Meridian

Colson Whitehead, The Intuitionist

Richard Wright, Native Son

PHOTOGRAPHY

Mark Clennon

John Edmonds

Latoya Ruby Frazier

Gordon Parks

Carrie Mae Weems

*=Featured in my “5 Ways to Stay Woke This Black History Month” blog post from 2019